25th Year Of Publishing In Mother Tongue With Bans and Awards: Avesta Publications

We talked to Abdullah Keskin, the Editor-in-Chief of Avesta Publishing whose 40 books among which two of them are Kurdish have been banned until today, whose warehouse in Sur had been burnt down, and who have difficulty participating in many book fairs after the end of the solution process on the 21st of February, World Mother Tongue Day.

When we look at the times that Avesta was founded, how did the idea of starting publishing in Kurdish in the 90s when the pressures were the most, how did Avesta begin its life?

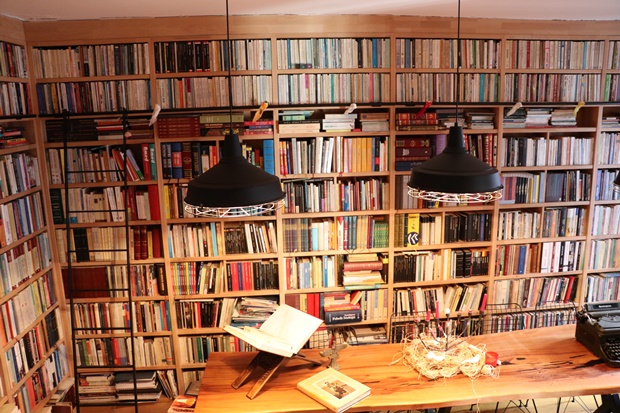

We founded Avesta at the end of the year 95. Actually, I had previously worked as a editor and journalist in several publishing houses. But I always felt like doing publishing on my own. I was onto that. Because I believed that real changes would happen with books. We thought that we should start somewhere with the encouragement of many people around us, especially Mehmed Uzun. If we had waited for a businessman to come and invest or conditions to occur, Avesta would probably not have been established for another 20 years. Despite all the shortcomings, problems and prohibitions, we began. In 95, 3 books about Kurds were published and then banned. Books, magazines and tapes that were published consecutively with the lifting of the ban on speaking Kurdish in 91 caused great excitement. But on the other hand, this excitement faded in a short time as it was not founded on well preparation and with serious labor. We started publishing with 4 Kurdish books now in order to feel that excitement once again. We have reached about 680 books today. I think we will exceed 700 at the end of the 25th year.

Considering that the Kurdish speaking ban was just lifted when you started publishing, didn’t you find it difficult to get a source in Kurdish at that time?

The literacy rate in those years was almost non-existent. Kurdology departments have been opened in several universities for the last few years. If we do not consider those who graduate from those departments, Kurdish has been an illiterate language until now as well as its authors, publishers and readers. I don’t know if there is another example of this in the world. We have published so many books, but I even saw the Kurdish alphabet for the first time in my 20s. It was as if I made a great discovery or found a treasure. I stayed home for a couple of weeks with a few Kurdish books, some story books and an alphabet, and read them all. Actually, we had nothing then. Before 80’s, few journals and books were published, although their numbers were very few. But it was not even possible to find them. Although some of the books published were brought from abroad, especially from Sweden were able to come, it came with mail with great difficulties, or it was a great privilege if somebody brought them by risking themselves and if you could reach a copy. The copies were then duplicated and distributed among people. A small amount of material was able to be formed at 95.

What we thought at first was this: People’s mother tongue was even prohibited as a spoken language. This caused a great destruction. Everyone wanted to claim their language somehow, wanted to speak in their mother tongue in their daily life, but this was not enough. While presenting the reader with a Kurdish novel, a research book or poetry, we were looking at how it was written as much as what was written. We were very sensitive about that. We had a lot of text coming. But most of them were problematic. We addressed to texts made up of other dialects of Kurdish through translation. On the other hand, there was a very serious deficit in history and research genres. However, there was great interest. We tried to create a certain literature by turning our hands to old travel books, memoires and contemporary research.

What about Kurdish book prohibitions?

Nobody could ever perceive this, neither inside nor outside, neither Kurds nor Turks neither the ones in Europe. How a language can be banned on the streets or at home in the late 20th century? When that ban was lifted, everyone acted as if the ban on publishing was lifted. Books, periodicals, magazines and books started to come out one after another. Until the start of negotiations with the EU in 2002, all Kurdish books we published between 95-2002 could have been banned. The state did not interfere much with that area at that time. 40 of our books have been banned so far. All of them are in Turkish except two. When you ban a book in Kurdish at that time, that book needed to be judged. The judges and the prosecutors did not speak Kurdish. A sworn translator was required, it had to be translated into Turkish. There were a few such examples. For example, İhsan Colemergi had an epic book called “Cembeli”. This was first published in Sweden. When the book came here, the police confiscated it and the trial was held in İzmir. The court asked the author to translate the book into Turkish. Then the trial ended in nonsuit. In other words, the habit of the state was about ignoring it. Because when you ban the book in Kurdish, you give it an international legitimacy. Therefore they did not do that much.

When was your first Turkish book banned?

Our first book was banned in 97. Then the Turkish books that we had published started to be banned one after another. The first banned book was Emir Hasanpur’s ‘State Policies and Language Rights Related to Kurdish Language’. In fact, it was a book that addressed those issues. Mehmet Aktaş’s book ‘Sesime Gel’ and Celadet Ali Bedirhan’s books were banned as well. In general, after the ban, it was reprieved for 3-5 years, provided that the same ‘crime’ would not be repeated. Of course, we never committed the same “crime” before the end of that given period, and the prohibitions and trials began again. It was a vicious circle. It lasted until 2007. We objected when one of our books was banned in 2007 and it was nonsuited.

40 of your books have been banned so far. Has there been any easy period concerning your publications?

No prosecution was brought against us in that 11 years between 2007 and 2018. In 2018, rumors started. The bookstores said that our books were banned and collected. But we didn’t know anything about that. A few months after the ban, a notification came to us. In an house raid carried out for another reason in the district of İdil in Şırnak, 9 different books that were published on different dates were banned. Between 2018 and 2019, a book that was in found in a prison during a body search was then banned. In a period of 1.5 years, a total of 14 books were banned this way. Our books were banned for reasons that even lawyers had trouble understanding. Moreover, we could not get a proper response even to our objections. It was a very uncertain period.

Have you considered giving a break in a period where bans were that much?

Let’s say we gave a break for a while for reasons such as prohibitions or economy. Still, nothing would change. Because a book that was published 20 years ago, on which you were put on trial, punished and acquitted is forbidden at once when found at some house. We have difficulty understanding what kind of situation we are facing. On the other hand, the books we think will be banned when preparing for publishing are not.

So, when we get back to the readers, how is your reader profile right now compared to the period you began?

In the last 25 years, the publishing house has created its own reader profile. Generally, university students are interested in books. If we limit the studenthood to 5 years, 5 different university generations have passed since the foundation of Avesta. During this period, the Kurdish situation experienced very different periods. But this 25 years, that is, from 91, when the ban on speaking Kurdish was lifted, is a first in terms of stability in modern Kurdish history. When we look at the history of Hawar, Ronahî, Kurdistan, Jîn, it was much shorter. During the Revolutionary Eastern Cultural Hearts period, there were very serious periodical publications and books were published from 1974 until 80’s coup. But it took 6 years. Now there is continuity since 91 in the means of our publication house’s history. Currently, many of our readers who closely follow us are of the same age with Avesta. Moreover, it’s a dynamic and young reader profile. This is a proud situation for us. It makes you feel that what you do doesn’t go to waste. We can see this very clearly in book fairs and meetings. Especially between 2007 and 2018, there was an increase in terms of both books and readers. In other words, until 2016 until clashes took place in cities, Kurdish Language has experienced a consistent boom episode.

Apart from this bright era, there were times when you got negative responses especially when attending fairs. How does this affect you when reaching to the readers?

There are two types of book fairs. The first is trade fairs such as TÜYAP. We do not have such problems at TÜYAP. However, costs at TÜYAP have increased so much that the game is not worth the candle. The second and a more problematic area is the fairs organized by local governments and provinces. We have serious problems in participating in fairs such as Siirt, Batman, Van, Urfa and Kadıköy book fairs. Of course, we do not have a concern to attend all fairs, but we try to be at the places where we have a certain reader profile. For example, in Kadıköy, the municipality responded very interestingly. Although we had a very serious reader potential, we did not know about Van book fair the first year. In the second year, we made an agreement, and although we had our stand, our place was reduced. We were not informed. We learned this situation from other publishers. When we objected, they said, “We will get back to you.” Then they told us that that was what they could do. So there is a very serious discrimination here. This is due to intolerance towards the Kurdish language and its readers. Moreover, in these cities we mentioned, the publishing house has corresponds to certain readers. Despite this, they are constantly excluding us without any serious reasons. If they could do nothing, they reduce our stands. This is very humiliating. A publisher with 100 books is given a big island, while Avesta, which has about 700 books, is given a small area. We mostly oppose to this. Although our readers would be damaged, we try not to accept this type of inferior treatment. Apart from us, almost every Kurdish publishing house has similar problems. Apart from the problems caused by places, there may be times in which we experience problems because of the readers. Sometimes when a reader sees a Kurdish book, he/she could swear or harass us.

This inferior treatment is actually towards Kurdish Language, isn’t it?

Of course, maybe I called it as inferior treatment, but it is far off. Where state TV channel broadcasts 24 hours a day, Kurdish in the Turkish Grand National Assembly can be written to the minutes as an “incomprehensible language”. Although some positive steps were taken for a period of time, this did not continue. Even back steps were taken…

Is your distribution network also limited due to Kurdish language?

We tried hard to expand our distribution network. We did not make sales in our own offices for a long time so that everyone could go and buy the books from bookstores. But the Outlook on Kurdish, Kurdish literature and language affects this network. When there is a very simple problem, bookstores return our books. In some places, our books are returned because the reader goes and tells them not to sell a book. The publishing house or the bookstore doesn’t even want to distribute our books. Moreover, even though we make commercial concessions, they do not want to distribute Kurdish books in particular. It is a very problematic area and we do not have the power and potential to develop an alternative to this.

Bizi Takip Edin